MEDICINAL PLANTS IN WARTIME

Plants were studied from the earliest times not for their beauty, or as foodstuffs, but for their medicinal properties; botany was part of a medical training long before it became a university subject in its own right. From Padua (1545) to Oxford (1621), universities established their own botanic (or physick) gardens, providing the materia medica which students would learn to recognise before being taught about the effects of plant extracts on human physiology.

By the eve of World War I, however, botany had become a subject worthy of study in its own right. As I told in Harry Marshall Ward and the Fungal Thread of Death, the ‘New Botany’ forged in German laboratories had recently been introduced to Britain. The biochemistry and physiology of plants were being studied in their own right, as was their ecology.

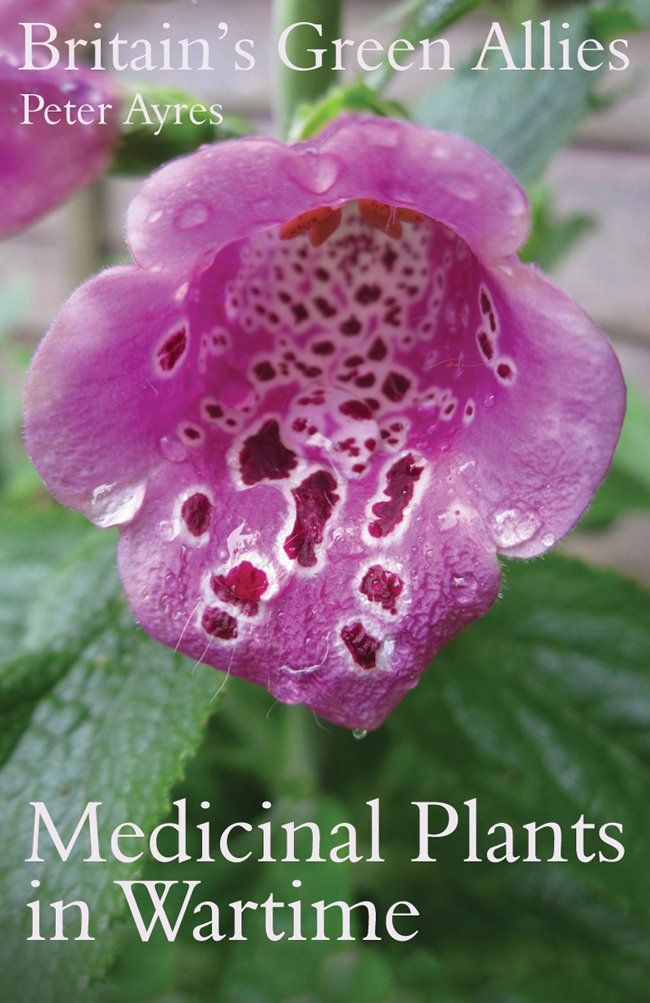

In 1914, and again in 1939, Britain’s supply of vital drugs and antiseptics needed by both its armies and its civilian population was cut off because German pharmaceutical companies dominated world markets. The drugs most difficult to replace were those extracted from plants, such as morphine from blue poppies, digitalis from foxglove, and atropine from deadly nightshade, because most of these plants were cultivated either in Germany or in lands controlled by its allies.

Britain’s Green Allies uses contemporary newspaper articles, government documents and personal accounts to tell how, although the lessons of WWI were promptly forgotten before having to be re-learned in WWII, Britain succeeded in maintaining an adequate supply of the key drugs and other plant-based medical supplies in both wars. Britain did this by strengthening its own pharmaceutical industry and by utilising both its native plants and the botanical resources of its empire.

Government, growers, the pharmaceutical industry, university researchers, and the public – members of the Women’s Institute, Boy Scouts, and Girl Guides – all did their bit to win their war.

Copies of the book are available from the author [ayres44@btinternet.com]. Price £12.50, plus £3.00 post and packing].

Further pages examine the Oxford Medicinal Plants Scheme of World War II, then, the Biology War Committee of WWII, a group whose work was concerned with more than medicinal plants.

We begin, however, with "The Great War", or World War I, and four little known women who made significant contributions to the supply and use of plant-derived medicines. In contrast to the ‘Women Inspired by Marshall Ward’ – see elsewhere on this site – who were academically trained botanists, the four here essentially taught themselves.

At their centre was the oldest, Maud Grieve, who made herself a knowledgeable, practical plantswoman and an inspirational teacher. One of her helpers was Edith Gray Wheelwright, an energetic campaigner for women’s suffrage. She and Ada B Teetgen were prolific writers, of both fiction and non-fiction. While Teetgen used one of her books to raise money for a hospital in Canada, the last of the four women, Hilda Leyel, raised money to support old and injured soldiers.

What united the women were medicinal plants and war.